Working as a nurse during the pandemic has been compared to going to war. The overwhelming stress and high stakes can leave nurses exhausted and emotionally strained.

David Bracho is a nurse and combat veteran that served two tours in Afghanistan. He sees the parallels that exist between serving on the frontlines and working in the COVID-19 ward. Now he’s helping his colleagues recover from post-traumatic stress disorder using the same programs he participated in as a soldier.

Going to War with COVID-19

According to a survey of more than 6,500 critical care nurses from the American Association of Critical Care Nurses, 92% said the pandemic has depleted the nursing workforce, while 66% admitted they were thinking of leaving the field altogether.

Branco says nurses are often picking up 16-hour shifts “just to keep the patients safe and alive.”

He said the military has reserves that will fill in for soldiers when they need a break and want to return home.

“When the military gets deployed for nine months to a year, we have relief,” he said. “There’s someone that’s gonna relieve us from our duties (so we can) go back home.”

But there is no relief in the healthcare industry.

Branco says this kind of emotional trauma will last for years. “There’s a huge amount of PTSD … and these nurses are expected to just work through it,” he said.

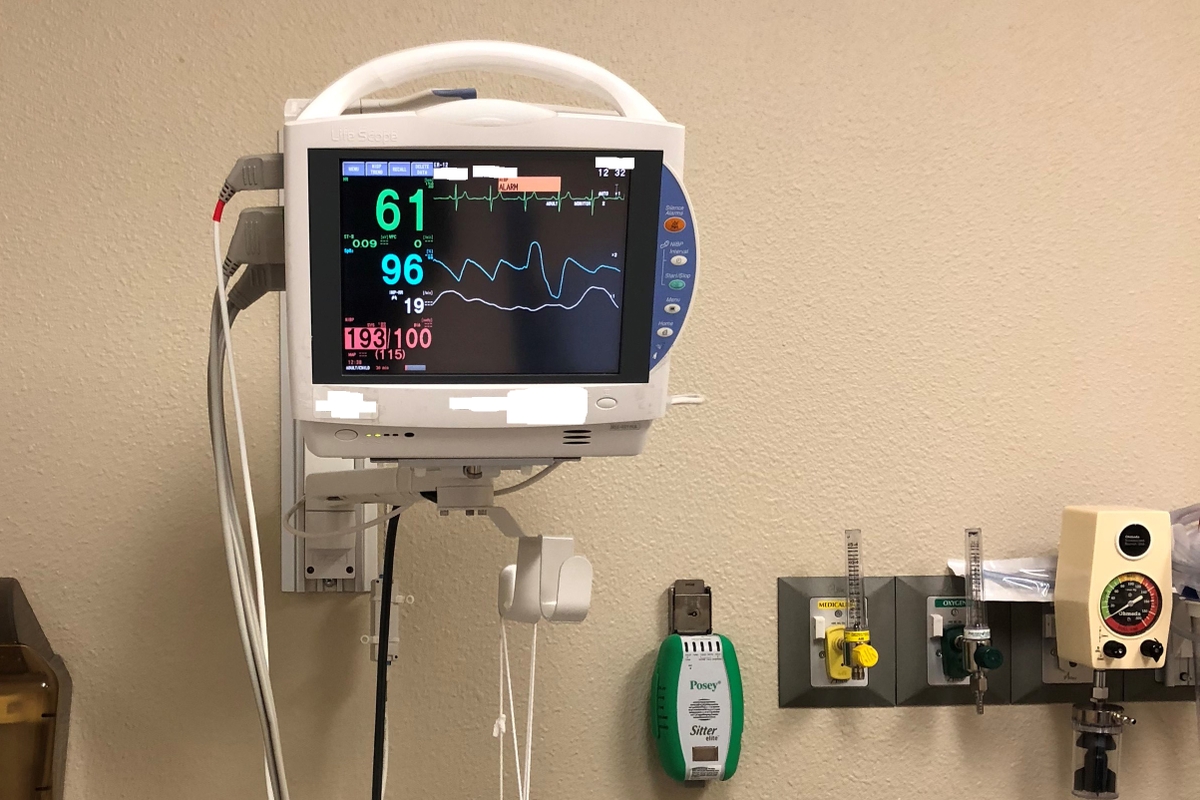

He currently works in the COVID-19 ward at Rush Medical Center in Chicago. The hospital is using temporary workers to fill in the gaps for the first time in 20 years, according to a facility spokesperson.

Rush recently implemented the Growing Forward program, a form of group therapy, which is the same treatment given to soldiers with PTSD returning from the frontlines. Participants attend six 30-minute sessions and are encouraged to journal and talk openly about their emotions while they learn about healthy ways to decompress. The program is being overseen by Mark Schimmelpfennig.

“When I was able to say, ‘Hey, you’re fighting a war against an enemy that you can’t see, feel, touch, hear or taste and it’s kicking our butts,’ they got it,” Schimmelpfennig said. “The cumulative trauma of dealing with that day after day after day after day, through surge after surge — there’s going to be a cost just like when a combat soldier goes outside the wire.”

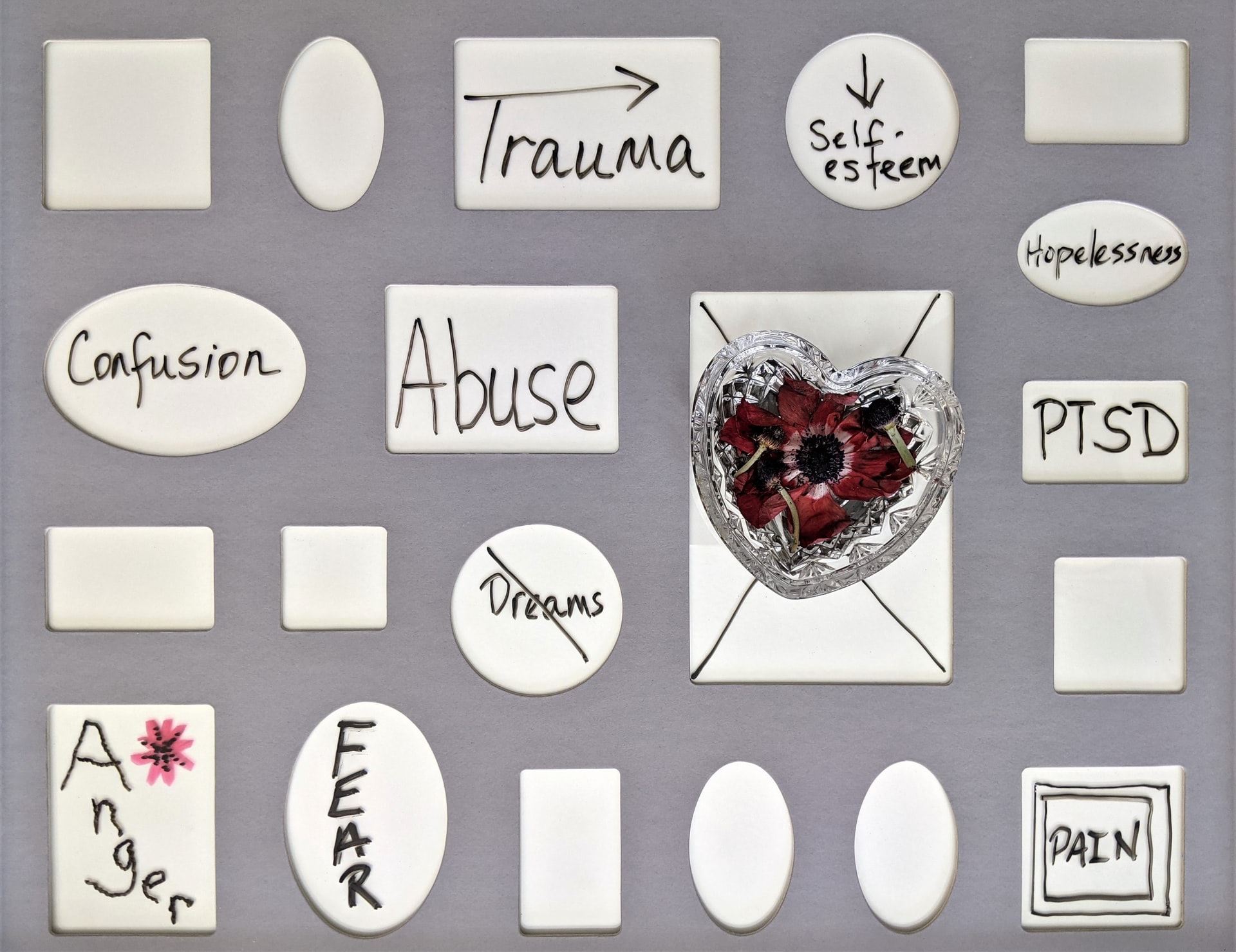

Kim Sangster, Bereavement Support and Educator Coordinator, started the program in August as a way of helping those caring for COVID-19 patients.

She says every session focuses on a particular theme, such as self-compassion. The participants leave every session with an object or something that reminds them of what they learned.

“We choose self-compassion over self-esteem because self-compassion is what we need to be able to create space so that we can feel really tough and complex feelings and deal with tough stuff,” said Sangster.

Schimmelpfennig also teaches nurses to stomp twice and breathe, which can help them go from a ten on the stress scale down to a seven. “Seven is still not very good, but you can get your job done,” he said.

He also runs into lots of nurses that feel unworthy of the “hero” title. He says this reflects a moral injury, which is when someone fails to do something one believes they should have done or when someone does something that goes against their core beliefs and values. It’s an invisible wound that affects thousands of soldiers.

“Every nurse here is a nurse because they want to help take care of people,” Schimmelpfennig said. “And so, when they are in situations where they’re not sure if what they’re doing is going to work, even though that’s the latest and greatest information from the hospital or the CDC, (they question) ‘Am I up to this task?'”

Melissa Gerona has been a nurse at Rush for 26 years. She says she’s cried more in the last two years than she has over her entire career.

“I’ve seen more tears shed on this unit — and I have my own — than ever before,” she said. “I couldn’t tell patients that you’re going to get better because at that point early on, we didn’t know who was going to get better. We’ve been through something now, all of us. And now we are doing more with less. Nurses have left the bedside.”

Despite the added emotional toll of the job, Gerona vows never to quit.

“My fear is that we’re going to have to do this again. Every time there’s a surge and I’m putting on my scrubs in the morning, I am always kind of in disbelief,” Gerona said. “I do feel like it’s a war. I stay because of my coworkers and my patients.”