Patients with an aggressive form of breast cancer may soon find relief from an unlikely source, the venom of honeybees. A recent study from Australia found that the venom killed cells for the triple-negative breast cancer in under 60 minutes. This type of cancer is one of the hardest to treat, and the researchers believe this humble ingredient may contain clues to a brighter future.

The study, published in Nature Precision Oncology, was led by Dr. Ciara Duffy of the Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research and the University of Western Australia.

The idea of using honeybee venom for medicinal purposes has been around for years. In 1950, researchers began using it to kill tumors in plants. But it has also proven effective in treating various forms of cancer, including melanoma.

But Duffy explains the study marks the first time it was tested against every type of breast cancer cell, as well as normal breast cancer cells. Duffy and her team used the venom and a synthetic version called melittin and compared the results.

Melittin is the molecule that creates the painful sensation of a bee sting. They found that both were effective against triple-negative breast cancer and HER2-enriched breast cancer cells. One type of venom in particular killed 100% of the breast cancer cells in 60 minutes without damaging the healthy ones.

“The venom was extremely potent,” Duffy said. “What melittin does is it actually enters the surface, or the plasma membrane, and forms holes or pores and it just causes the cell to die.”

For the study, the researchers collected 312 honeybees and bumblebees in Perth, Australia; England; and Ireland.

“Perth bees are some of the healthiest in the world,” Duffy said.

The bumblebee venom had no effect on the cancer cells, but the honeybee venom proved surprisingly effective. Duffy said the venom’s country of origin had no impact on its ability to fight cancer.

Researchers say the melittin interferes with the cancer cells’ messaging system, which stops the cancer from spreading to other parts of the body.

“We looked at how honeybee venom and melittin affect the cancer signaling pathways, the chemical messages that are fundamental for cancer cell growth and reproduction, and we found that very quickly these signaling pathways were shut down,” says Dr. Duffy.

However, they still don’t fully understand how the venom kills the cancer cells.

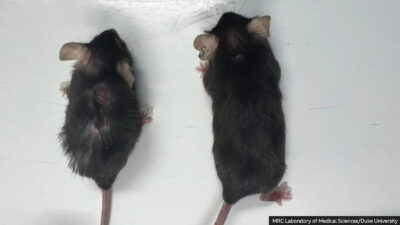

The treatment could be used in combination with chemotherapy and other existing cancer therapies by making the cancer cells more susceptible to treatment. Duffy found this combination to be effective in treating cancer cells in mice.

But experts say killing cancer in a lab is not the same as treating it in a human being.

“It’s very early days,” said Alex Swarbrick, associate professor at Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Sydney. “Many compounds can kill a breast cancer cell in a dish or in a mouse. But there’s a long way to go from those discoveries to something that can change clinical practice.”

Duffy and her team acknowledged that more work needs to be done before the technique is used on humans.

“There’s a long way to go in terms of how we would deliver it in the body and, you know, looking at toxicities and maximum tolerated doses before it ever went further,” she told reporters.

But the healing effects of the honeybee venom could be a game-changer when it comes to treating certain types of cancers.

“Honeybee venom is available globally and offers cost effective and easily accessible treatment options in remote or less developed regions. Further research will be required to assess whether the venom of some genotypes of bees has more potent or specific anticancer activities, which could then be exploited,” the researchers wrote in the press release.

It also highlights the power of natural remedies.

“It provides another wonderful example of where compounds in nature can be used to treat human diseases,” said Peter Klinken, Western Australia Chief Scientist Professor, who was not involved with the study. “This is an incredibly exciting observation that melittin, a major component of honeybee venom, can suppress the growth of deadly breast cancer cells, particularly triple-negative breast cancer.”